Once a person decides to make a behavior change, the first several days and weeks are critical. Motivation and energy are high. Commitment is at its peak. Positive and motivating change often occurs.

Eventually, however, relapse occurs.

In fact, relapse is a normal part of behavior change. And the clients who are most likely to work through it and continue on their behavior-change journey are those who recognize that relapse happens, take steps to prevent and minimize it, and ultimately acknowledge when it occurs and treat it not as a sign of failure, but rather as a learning opportunity.

Health and fitness professionals can help clients succeed in making long-standing behavioral changes to reach and sustain their goals by recognizing triggers for relapse, preparing clients for these triggers and practicing how to address them, and coaching clients on how to resume an intended behavior change after relapse occurs. Here’s how:

Recognize Relapse Triggers

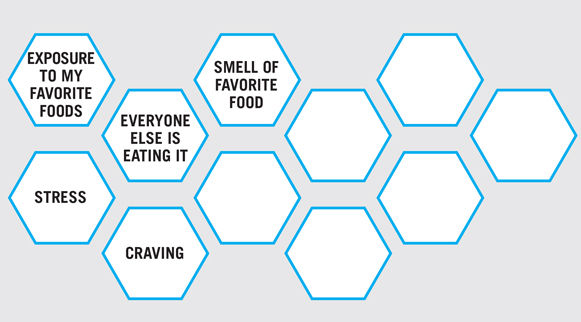

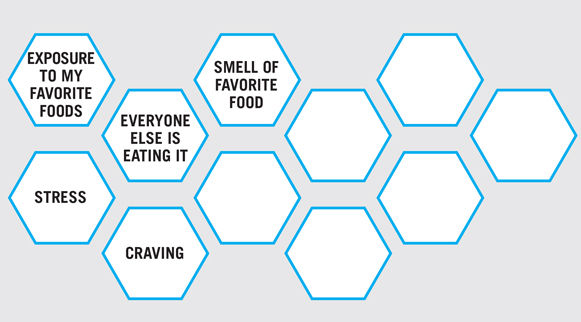

Clients may identify different triggers for relapse. It is helpful to have a discussion about what these triggers might be. One way to help clients address triggers could be through a bubble sheet. For example, fill in a few circles ahead of time with common triggers and leave a few blank. Say, “Many of my clients identify triggers such as _________. Do you think any of these might be a trigger for you, or perhaps there is something different?” For example, common triggers for people making dietary changes include exposure to highly palatable foods; food-associated cues such as an ad for a favorite food, a smell, or an event where that foods was consumed in the past; and stress. A bubble sheet for someone working to make healthful dietary changes might look like this:

[Download a PDF (9K) of this worksheet.]

Practice Relapse-management Strategies

After a client has thought about possible triggers for relapse, it is helpful to explore in more detail how to manage or avoid such triggers. For example, an open question such as, “How might you avoid these triggers?” may prompt a client to list several ways he or she could change the home environment and daily routines to better support adherence to the positive behavior change underway. This approach, which forces a client to problem-solve, is more effective than offering non-specific advice such as, “Change your environment to minimize triggers.”

Prompt a client to explore in more depth situations that might be particularly difficult or that the environment cannot easily be rearranged to avoid. For example, your client may have an unsupportive spouse who refuses to remove the client’s favorite unhealthy food from the home environment. Role-play and rehearse this situation, using reflective listening to prompt the client to identify possible solutions and develop a plan to address that situation when it occurs.

Evidence also suggests that one of the strongest predictors of sustained behavior change is a high degree of self-regulation (Teixeira et al., 2015). You can help your clients develop these self-regulation skills by building in self-monitoring, goal-setting and planning strategies into their behavior-change interventions.

Learn from Relapse Experiences

Most clients will experience a relapse within the first several months of a substantial behavior change. It is important to have a strong nonjudgmental relationship in place so that clients will be willing to explore the relapse with you in more detail.

Key questions to help clients learn from the experience and avoid or minimize future lapses or relapses include:

What personal strengths helped you to manage this relapse and begin your change again?

What may have been a weakness that contributed to the relapse?

How might we work together to develop a plan to strengthen that weakness?

What might you do differently if placed in the same situation again?

Additionally, work with clients to strengthen their coping skills. For example, a client might practice asking for help, whether that is from a health or fitness professional or a peer network, such as a self-help group. In fact, self-help groups can be particularly effective as clients learn that they are not alone, about challenges that others experience and how others have developed coping skills, and also experience a safe place free of judgment.

It’s also important to recognize that clients who learn to practice self-care through strategies such as mind-body relaxation and meditation and providing themselves with small rewards throughout the change process experience greater success and resilience when working toward making a lasting behavioral change.

Resources

Melemis, S.M. (2015). Relapse prevention and the five rules of recovery. Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 88, 325-332.

Teixeira P.J. et al. (2015). Successful behavior change in obesity interventions in adults: A systematic review of self-regulation mediators. BMC Medicine, 13, 84.

Earn an ACE Behavior Change Specialty Certification

No matter how you work with clients and patients, effective coaching can further heighten the impact of your program. As an ACE Behavior Change Specialist, you will possess the knowledge of behavior-change philosophy and emotional intelligence and, most importantly, the practical, hands-on skills to put it to use. Our comprehensive learning experience incorporates expertise from renowned experts and pioneers in psychology and coaching to help you learn how to develop rich, productive relationships and guide people toward sustainable change in one-on-one, group and virtual settings.

Learn more >>

by

by